Singapore’s first White’s Thrush

Sin Yong Chee Keita and Raghav Narayanswamy

Discovery

In the late morning of 23 November 2023, a photo of a thrush was circulated around Singapore’s birding community that sent chills down the spines of many. A bird new to the nation was found in the Singapore Botanic Gardens (SBG), co-discovered by Ikson Siah, Keison Ma, and possibly other observers. (If you were also one of the initial finders, could you please submit a record to us mentioning so, as we’d really like to credit you properly!). It was first thought to be a Siberian Thrush, but the lack of a pronounced supercilium and dense scalings on the underparts and upperparts soon revealed that it was something else. Those who recognised the bird knew it was some sort of bird from the Scaly Thrush complex, but the photographs available were not sufficient to identify it initially.

Many who received the news visited the site to document the bird, but the main question everyone had was whether the bird was a Scaly Thrush or a White’s Thrush. Multiple excellent photographs that were taken thereafter allowed us to assess its identity and status. Below is the Singapore Bird Records Committee’s take on the bird.

The Scaly Thrush complex

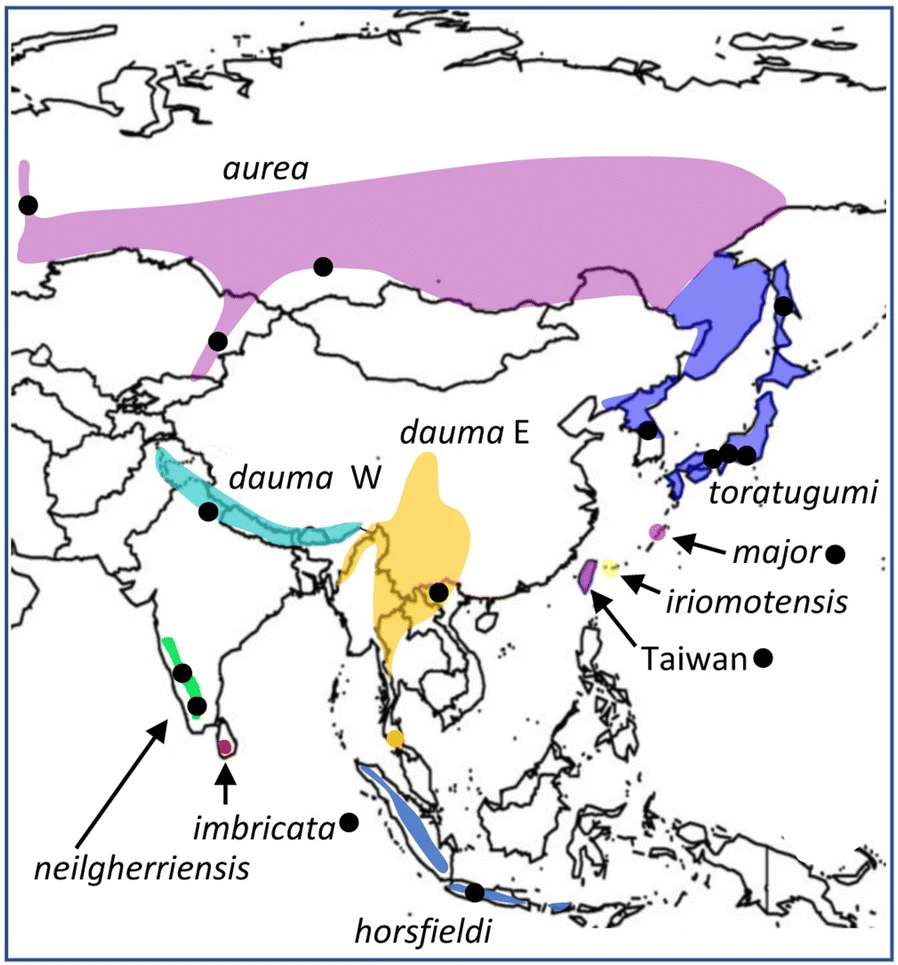

The distinctive scaled appearance of the bird indicates that it is one of the species from the Scaly Thrush complex (a complex refers to a group of (sub)species that are very similar looking to each other). Multiple similar species are recognised from the complex today including the Sri Lanka Thrush, Amami Thrush, Nilgiri Thrush, White’s Thrush, and Scaly Thrush. These birds all used to be called the Scaly Thrush until recent history. The first two species are endemic to their island ranges while the Nilgiri Thrush resides in the Western Ghats of southwestern India. These birds look distinctly different (by Scaly Thrush standards), and their wild occurrence in Singapore is more or less impossible due to their range and non-dispersive behaviour. The White’s Thrush on the other hand breeds in Russia and East Asia including Japan, and is known to be a long distance migrant to Indochina and the Philippines. It is also a well-established vagrant to Europe, with records as far as Iceland. In contrast, the Scaly Thrush has a wide range from the Himalayas to Indochina and is generally thought to be resident – but more on that later. A separate subspecies of the Scaly Thrush, sometimes spit as the Horsfield’s Thrush, is endemic to Java and Sumatra.

The thrushes that could potentially occur in Singapore based on their ranges are the Scaly Thrush and White’s Thrush. There are several subspecies involved in these birds that might make things confusing, and it doesn’t help that these birds are still so poorly understood. Here’s a quick summary based on current knowledge for the two species relevant to us, with the two most relevant taxa bolded.

TaxonRangeNotes

Scaly Thrush Z. dauma daumaNorthern Pakistan through Himalayas to northern IndochinaTwo taxa are sometimes recognised within Z. dauma dauma, dauma in the Himalayas and socia in southern China. These are indicated in the range map below as dauma W and dauma E, respectively. The western population is thought to winter in northern India, and eastern population to Indochina. The eastern population could potentially occur in Singapore.

Scaly Thrush Z. dauma horsfieldiMontane regions of Sumatra, Java, Bali, Lombok, SumbawaUnlikely to occur in Singapore given its highly sedentary nature.

Scaly Thrush Z. dauma iriomotensisIriomote IslandUnlikely to occur in Singapore given its highly sedentary nature.

White’s Thrush Z. aurea aureaBreeds Siberia through Manchura to Korea, long distance migrant to south China and IndochinaPossible to occur in Singapore as a southern overshoot given its highly migratory nature.

White’s Thrush Z. aurea toratugumiFar eastern Russia, Sakhalin, to Korea, Japan. Migrates to eastern China and Taiwan.Some records in the Philippines. While this subspecies could be considered, given its more eastern distribution, Z. aurea aurea is probably more likely to occur in Singapore. Additionally differentiating this subspecies from nominate aurea will be nearly impossible from photographs alone.

Could the range possibly be useful in suggesting one species or the other? Again, there is little information available. Initially we thought that White’s Thrush would be more likely to occur in Singapore, as it is the only known long-distance migrant in the species complex. All records from central Thailand are listed as White’s, and those with photos appear to be this species (see Identification). But the records in Peninsular Malaysia listed by Wells (2007) that are supported by measurements seem consistent with Scaly instead, and the Malaysian Bird Checklist only includes Scaly Thrush from Peninsular Malaysia and only White’s in Malaysian Borneo (MSNBCC, 2020). In sum, it is probably unsafe to favour either species on range, as the seasonal movements of Scaly Thrush are unclear right now.

Now that we’ve established that the species which could potentially occur in Singapore based on their ranges are most likely be the eastern subpopulation of Scaly Thrush Z. dauma dauma (=socia) or the long-distance migrant White’s Thrush Z. aurea aurea, let’s dive deep into the key identification features.

Identification

Our first instinct, based on the resources we were familiar with, was to suggest that photographers try and get a photo of the spread tail so as to count the number of tail feathers – several sources list the presence of 14 rather than 12 rectrices (tail feathers) to be a diagnostic feature of White’s Thrush (e.g., Nishiumi & Morioka, 2009). Within a few hours, Francis Yap managed to photograph the tail in flight, showing 14 rectrices. However, upon further reading we found that this claim – that only White’s Thrush can have 14 rectrices – is contested. Some sources state the eastern population of Scaly Thrush (socia) can have 14 rectrices as well (Zheng et al. 1995).

Doubts over the validity of the tail feather count for identification are reinforced by an example from northeast India, a bird with measurements and wing formula suggesting Scaly Thrush, but with 14 tail feathers; this record is within the range of socia as illustrated in Weir (2018). (Praveen et al., 2023). Mees (1977) also provides measurements for three Scaly Thrush records from Thailand with 14 rectrices. Lastly, another record from Peninsular Malaysia listed in Wells (2007) is likewise of a bird with 14 rectrices with measurements aligning to Scaly Thrush and not White’s Thrush. These examples lend credence to the theory that conclusive identification of White’s may not be possible purely on the basis of tail feather count.

With the tail feather count aside, what are the features that remain? Some sources refer to the auricular crescent, or dark patch behind the eye, which is said to be more distinct in White’s compared to Scaly. Photos we examined indeed suggest the crescent appears on average larger and more distinct in White’s, but with quite extensive overlap.

The most reliable feature separating the two species is the wing formula. This is easiest to gauge on birds in the hand, but is sometimes possible from good field photographs too. It can get pretty confusing sometimes, so bear with us here. It may be easier to refer to the annotated photos below along with the text. Note: On this site, we often count the primaries outwards; i.e. with p1 adjacent to the secondaries and the outermost primary typically being p9 or p10, but here we follow the ascendant numbering sequence adopted by the publications that deal with this species complex. p1 is therefore the outermost primary.

As discussed by Praveen et al. (2023), the two species consistently differ in the relative lengths of the primary feathers. Counting from outer primaries to inner primaries, for both species, the 6th primary feather (p6) is much shorter than the fifth (p5). Where the two species differ, however, is in the length of p2 relative to p4, p5, and p6. In Scaly Thrush, p2 falls between p5 and p6 in length, whereas in White’s Thrush p2 is longer than p5 and approaches the length of p4.

In the photo below of the SBG bird, we can see a row of seven neatly aligned primaries (p4–10) and one primary sticking out, with two primaries hidden, for a total of ten primaries. Of course, none of the comparisons above can be used unless we can see p2. It would be pretty helpful if that last exposed primary was p2 – and we were indeed able to conclude that it is p2 – but why?

It’s not p1, because p1 would be much shorter; primaries 2–5 are the longest in Scaly-type thrushes. Understanding why it is not p3 is more difficult and involves the feather’s emargination. Put simply, emargination refers to indentations on the outer part (outer web) of the primary feathers. You can find a nice close-up depiction of emargination here, with Common Chiffchaffs and Willow Warblers. Notice how the unemarginate feathers appear to have a straight outer edge while the emarginate feathers have a sharp narrowing in the outer edge. For this bird, the photo depicts the lone primary clearly enough to show that the feather jutting out is unemarginate, with a straight outer edge; in both White’s and Scaly Thrush, p2 is unemarginate and p3 is emarginate, so this lone feather must be p2 and not p3.

As shown in the annotated figure below, for the SBG bird, p2 is clearly longer than p5, approaching the length of p4. This is a solid feature pointing to the identity as a White’s Thrush.

The bill size of the SBG bird is also suggestive of White’s, which has a longer, heavier bill compared to Scaly. Despite much variation within White’s, even the birds with the smallest bills appear to have larger bills than in Scaly. A few examples below:

- Scaly Thrush from Chiang Mai, Thailand. Note weak, short bill.

- Scaly Thrush from Yunnan, China. Again, note the weak bill. The wing formula is also evident on the first image, with p5 noticeably longer than p2, unlike in the SBG bird.

- White’s Thrush in Bangkok, Thailand. A particularly large-billed individual.

- White’s Thrush in Nakhon Pathom, central Thailand. This one has a smaller bill than the previous bird, but still larger and longer than Scaly.

The bird at the Botanic Gardens has a thicker bill than would be expected from Scaly. Similarly, the bill length is more consistent with White’s than with Scaly.

On the basis of the evidence provided and after consulting with James Eaton from our advisory panel, as well as Jonathan Martinez, our Records Committee accepted the record as a White’s Thrush. It represents Singapore’s first record and, as far as we are aware, the southernmost record globally for this species.

Acknowledgements

This thrush only showed for one day, so we’d like to extend a huge thanks to Ikson, Keison, and the others who found the bird (again please submit a record to us and let us know who you are!) for the very quick sharing. Without that, the bird would likely have remained painfully unidentified. Additionally, your sharing allowed our community to collectively enjoy the birding experience. We thank those who posted their photos online, and Daryl Yeo, Francis Yap, and Jared Tan, who contributed photos to this article.

Many new species have been found in Singapore over the past few years thanks to the ever-increasing pairs of eyes in the field. Whenever you’re in doubt of the bird identification, please always feel free to ask! You’ll never know when you’ll find a national mega. Our partner Facebook group Bird Sightings is one of the platforms where you can ask freely.

The Records Committee would also like to thank James, Jonathan, and several others for assisting us with the identification features. We are grateful to Praveen J., Paul R. Sweet (AMNH Ornithology), and Rahul Khot (BNHS), for allowing us to reproduce specimen photographs originally published on Indian BIRDS, and to Jason Weir for allowing us to reproduce the range map of the Scaly Thrush complex originally published on Avian Research (CC BY 4.0).

References

Collar, N. D., Christie., A., Kirwan., G. M., & del Hoyo, J. (2020). Scaly Thrush (Zoothera dauma), version 1.0. In S. Billerman, M., Keeney, B. K., Rodewald, P. G., & Schulenberg, T. S. (Eds.), Birds of the World. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.scathr8.01

del Hoyo, J., Collar, N. D., Christie., & A., Kirwan., G. M. (2020). White’s Thrush (Zoothera aurea), version 1.0. In S. Billerman, M., Keeney, B. K., Rodewald, P. G., & Schulenberg, T. S. (Eds.), Birds of the World. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.scathr2.01

Malaysian Nature Society – Bird Conservation Council (MNSBCC). (2020). A checklist of the birds of Malaysia, 2020 edition. Link

Mees, G. F. (1977). Additional records of birds from Formosa (Taiwan). Zoologische Mededelingen, 51(15), 243–264. Link

Nishiumi, I., & Morioka, H. (2009). A new subspecies of Zoothera dauma (Aves, Turdidae) from Iriomotejima, southern Ryukyus, with comments on Z. d. toratugumi. Bull Natl Mus Nat Sci Ser A Zool, 35(2), 113-124. Link

Praveen, J., Maheswaran, G., Naskar, A., Alam, I., Majumder, A., Khot, R., Hegde, V., Sweet, P. R., & Trombone, T. T. (2023). Addition of White’s Thrush Zoothera aurea to the South Asian avifauna. Indian BIRDS, 18(6), 181-184. Link

Robson, C. (2014). Field guide to the birds of South-East Asia (Second Edition). Bloomsbury Publishing, London.

Wells, D. R. (2007). The Birds of the Thai-Malay Peninsula (Vol. 2). Christopher Helm, London.

Weir, J. T. (2018). Description of the song of the Nilgiri Thrush (Zoothera [aurea] neilgherriensis) and song differentiation across the Zoothera dauma species complex. Avian Research, 9(1), 1-7. Link

Zheng, Z. X., Long, Z. Y., & Lu, T. C. (1995). Fauna Sinica, Aves. Vol. 10. Passeriformes, Muscicapidae 1, Turdinae. Science Press, Beijing. Link