What do Universal Studios, a raucous laughing call, and one of the longest-running behavioral studies of birds all have in common? No, this isn’t the start of a joke–all these identifiers actually refer to one unique bird, the Acorn Woodpecker.

Believed to be the inspiration behind Woody Woodpecker’s iconic call, the Acorn Woodpecker easily engages the imagination. With its unique social dynamics and unyielding focus on storing acorns the Acorn Woodpecker makes a distinct impression. If you are in oak country within their range, their red cap and white eye, waka waka-like calls, and often communal habitats may draw your attention.

Range and Migration

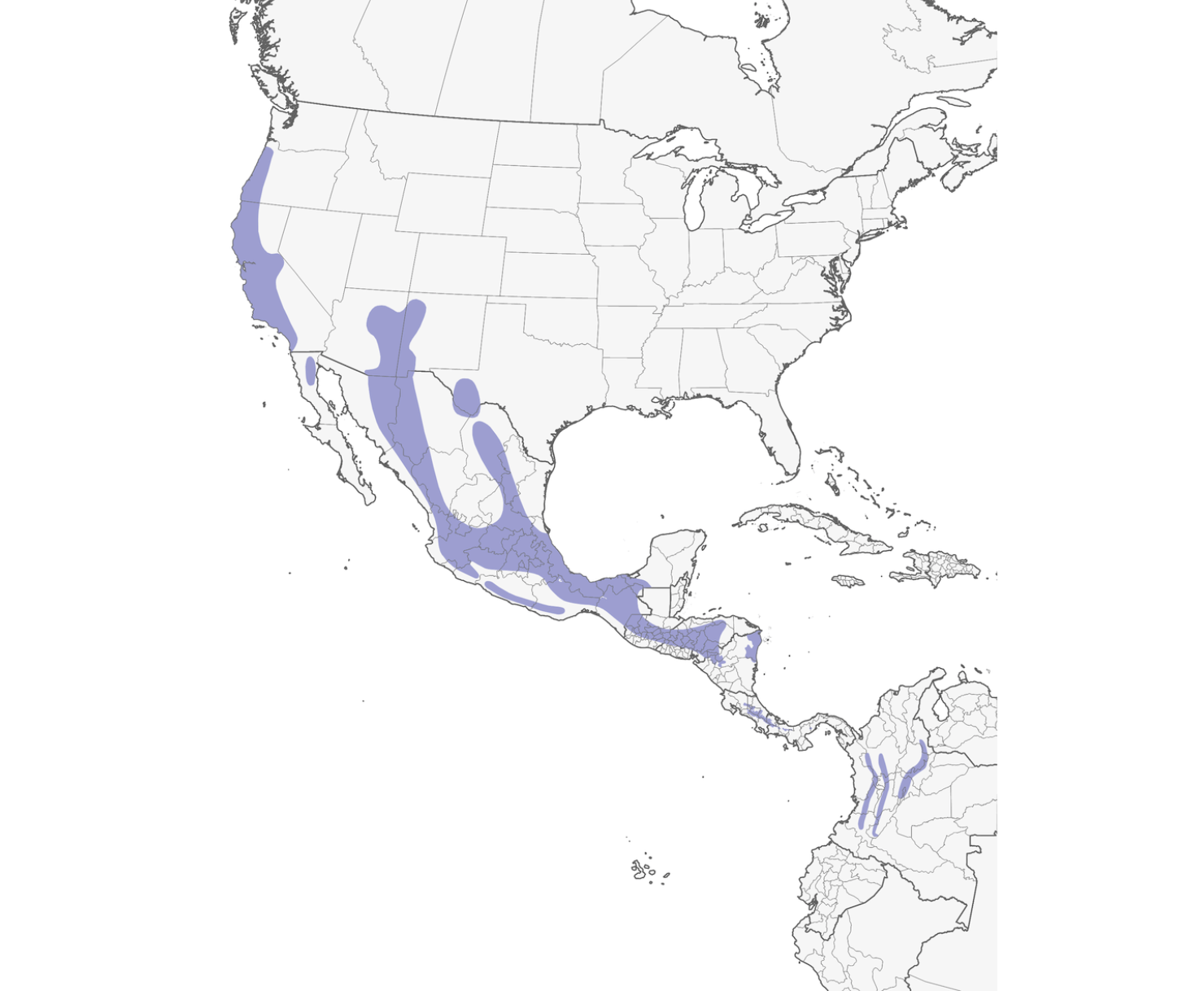

The Acorn Woodpecker (Melanerpes formicivorus) is typically a resident species found in select habitats from southern British Columbia to northern South America. Though most populations are non-migratory, if acorns are not plentiful or there is not adequate oak habitat, these birds may seek out new areas with more culinary options.

Within the Pacific Birds region, they are a common resident in parts of California and Oregon and to a lesser extent southwest Washington. They are also relatively tolerant of human activity so if you have oaks, you may be lucky enough to listen to and watch their unique antics.

Global Distribution of the Acorn WoodpeckerMap from Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Habits and Habitats

The Acorn Woodpecker is an oak woodland specialist, relying on oaks for food, shelter and nest cavities. In California and Oregon, and slightly into Washington, they are associated with oaks in the genus Quercus, often the Oregon white oak or the black oak. They prefer oak woodlands with a more open understory and rely on mature oaks for both food storage and nest sites. In a win-win arrangement, the woodpeckers are also helping distribute acorns that may seed new oak trees.

While other woodpeckers are usually seeking insects when they drill into trees, the Acorn Woodpecker feeds mostly on flying or terrestrial insects, seeds, and fruits as well as high-caloric acorns which they store for winter. They spend a significant amount of their time associated with granary trees–trees in which they bore holes or use natural notches and cracks to store acorns. According to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, these storage areas may have up to 50,000 acorn holes in them.

Bird Note also tells us that utility poles, fence posts, or the sides of barns will do in a pinch when a tree isn’t available. While not the only bird species to utilize or store acorns, this species certainly takes it to the extreme!

The communal habits of Acorn Woodpeckers are characteristic of the species.Arvind Agarwal © Creative Commons

Conservation Status

Even with a global breeding population estimated at 5 million birds, there is still a need to conserve this iconic woodpecker. As a species highly associated with oak habitats, there is concern for the species within regional or local areas and ongoing habitat loss and other environmental change elevate concerns about the species.

The Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife lists Acorn Woodpeckers as a sensitive species in the Willamette Valley and Klamath Mountains due to conversion and loss of oak habitats. Nature Serve’s overall species ranking is G5 (secure) but they rank the species as vulnerable in Oregon. While Washington’s populations are considered critically imperiled by Nature Serve, it is not a state-listed species since it is considered a peripheral species due to range expansion.

In addition to loss or degradation of mature oak trees, other threats to present population levels include slow oak forest regeneration, the introduction of European Starlings and–depending on location–a warming climate. As shown by the National Audubon Society’s climate scenarios map, an increase of +3 degrees Celsius could result in population loss across part of the species’ range, but climate change might provide favorable conditions elsewhere.

Managing for Oaks and Birds

In the Pacific Northwest, most remaining oaks are found on private lands. Saving mature oaks in residential and urban areas (every oak helps!) and working with landowners and managers on working lands to maintain oaks for birds will help sustain Acorn Woodpecker populations for the long term. Pacific Northwest oak habitats are also important to about 25 other bird species, and offer up an entire ecosystem for multiple species of plants, invertebrates, birds and mammals. And since people also love oaks, their conservation is a good deal all around.